We first stumbled across the quiet village of Burnham Thorpe in north Norfolk on a rainy day in 2009 that turned out to be Trafalgar Day. This was rather lucky because this village was the birthplace of Admiral Horatio Nelson. We returned earlier this year in April 2017, and found this beautiful, historic village little changed.

On 29th September, 1758, Horatio Nelson was born to Catherine (née Suckling) and Reverend Edmund Nelson in the old parsonage (no longer standing) in Burnham Thorpe. Apparently, a small metal plaque fixed on an outer wall near this the original location of this building commemorates his birth, but we couldn’t find it however hard we looked. (Disclaimer: it was raining, so we didn’t try all that hard!). We did, however, come across this rather wonderful ship-shaped (pun intended) climbing frame for local children.

Nelson lived in this village during his early boyhood and again soon after his marriage to Frances ‘Fanny’ Nisbet (1761-1831). Fanny was born on the island of Nevis, in the Caribbean, where she met and married Nelson in 1787 after a two-year long engagement. At the time, Nelson had command of HMS Boreas and was tasked with enforcing the Navigation Acts in the seas around Antigua. At first, I wasn’t going to mention the Navigation Acts. This is not because I didn’t think they were important, but, in my ignorance, I thought they were probably about something rather dull. This is not the case.

The Navigation Acts were a series of mercantilist laws imposed by the British government from the seventeenth century onwards. They were motivated by the soon-to-be defunct economic idea that a trade was a zero-sum-game in which one country could only grow richer by the accumulation of bullion through a favourable balance of trade at the expense of another. In practice, this meant the enforcement of rules which, for example, prevented the import of sugar from French plantations, or required that sugar from British plantations could only be carried in British ships. Indeed, a recurring concern about the East India trade in the period was precisely that it supposedly drained British wealth by encouraging the very opposite, i.e., the export of bullion to pay for Asian commodities.

The Acts were only repealed in 1849 following the long economic debate surrounding the repeal of the Corn Laws, which culminated in a new era of free trade: the Manchester School liberals, led by Richard Cobden (1804-1865), showed that people’s prosperity was in fact better served by a general lowering of prices through the removal of protectionist policies and the unrestricted expansion of international exchange. In essence, the idea was to end subsidies for producers at the expense of consumers.

See? I told you it was interesting!

The Lord Nelson pub

At the end of his period of service in 1787, Nelson returned to England with Fanny and they settled in Burnham Thorpe. It was only 6 years later, in January 1793, that he was recalled to service and given command of HMS Agamemnon. Just one month later, France declared war on Britain. Nelson sailed to the Mediterranean and, in September 1793, he met Emma Hamilton (1765-1815) in Naples while on a mission to request reinforcements against the French. Lady Hamilton was the wife of Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803), the British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples. It was after Nelson’s victory against the French at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, when Nelson was seriously injured, that they began their famous affair. In 1801, Emma gave birth to their daughter, Horatia Nelson (1801-1881). Descendants of Nelson and Emma are still alive today, which is a curious thought.

This would have been the perfect moment to include some images of paintings of the beautiful Emma by Romney. But, I won’t because everyone has seen so many of them. Instead, I include an image that stopped me in my tracks. When I was looking for information about Nelson, Emma and Horatia, I came across a photograph - let me repeat that - a photograph of Horatia Nelson aged about 59.

There is, surprisingly, a link between Sir William and the Hotung Gallery project that I have been working on. Hamilton was a great collector of antiquities, and he amassed a considerable collection during his time in Naples. A number of objects from his collection are now in the Department of Greece and Rome at the British Museum. In the Hotung Gallery, I decided to curate a section dedicated to Indo-Roman trade and some of the objects I have included are from Hamilton’s collection. I have planned a series of blogposts about this gallery, and will expand on this subject there.

Returning to Burnham Thorpe, a number of local men volunteered to serve under Nelson, and before Nelson joined his ship, he held a party in the local village pub, The Plough. The pub was renamed The Lord Nelson in 1798, after his victory at the Battle of the Nile.

- Open in 2009…

- …closed in 2017

We went into this pub on the afternoon of Trafalgar Day in 2009, but we were not able to drink to Nelson’s heath because we were told it was closed and they weren’t serving drinks. Disappointing. When we returned in 2017, we still didn’t get our drink because it had been repossessed in the previous year and, according to the Greene King website, is currently being refurbished while a new pub landlord is sought.

So, instead, I turn to the trusty internet. The famous ‘Nelson’s Blood’ was developed by one of the pub’s former landlord’s in the 1970s or so. It is a blend of rum (of course) and spices and, according to their website, ‘made to commemorate the drinking of the rum from around the body of Admiral Lord Nelson on the journey home from Trafalgar.’ Nice. I plan to order a bottle for Christmas.

All Saints’ Church

Our first port of call (I know, I know) was All Saints’ Church, Burnham Thorpe. Nelson’s father was rector of this church and Nelson was baptised here a few hours after his birth. The church is filled with objects that are linked in some way to Nelson, some directly and others somewhat more tangentially.

As you enter the church, the first thing you see is the 13th century white marble font in which Nelson was baptised. It is now flanked by two huge ensigns from the WWII battleship HMS Nelson.

- HMS Nelson ensigns

- Font flanked by ensigns

- Font Nelson was baptised in

Affixed to the wall on the right of the font and ensigns are two pieces of history. The first is a small, and rather innocuous, inscribed plaque, but a closer look reveals that it is made from oak and copper taken from HMS Victory. This was Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), and it was on this ship that he died. The inscription reads:

‘Thanks to the generosity of officers and men of the Royal Navy, and many other subscribers, the bell which was in use at the time of Lord Nelson, was restored and rung again on the 200th anniversary of his birth, September 29th 1958.

This tablet, made of oak and copper from HMS Victory was presented to commemorate the occasion.’

Above this plaque, is the framed ships crest from HMS Nelson. It was presented to the church in 1955 to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar.

As part of the restoration, which was completed in 1905 in time for the centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar, the Admiralty donated wood from HMS Victory to the church. This material was used to build the altar, lectern and rood screen.

Two other flags hang in the church: a Union Jack and an ensign. They were flown by HMS Indomitable at the Battle of Jutland (1916) in WWI.

- Union Jack

- Ensign

As an aside, All Saints church has the unique right to fly the white, pre-1801 ensign flag from its church tower. You can see it in the photograph of the church below.

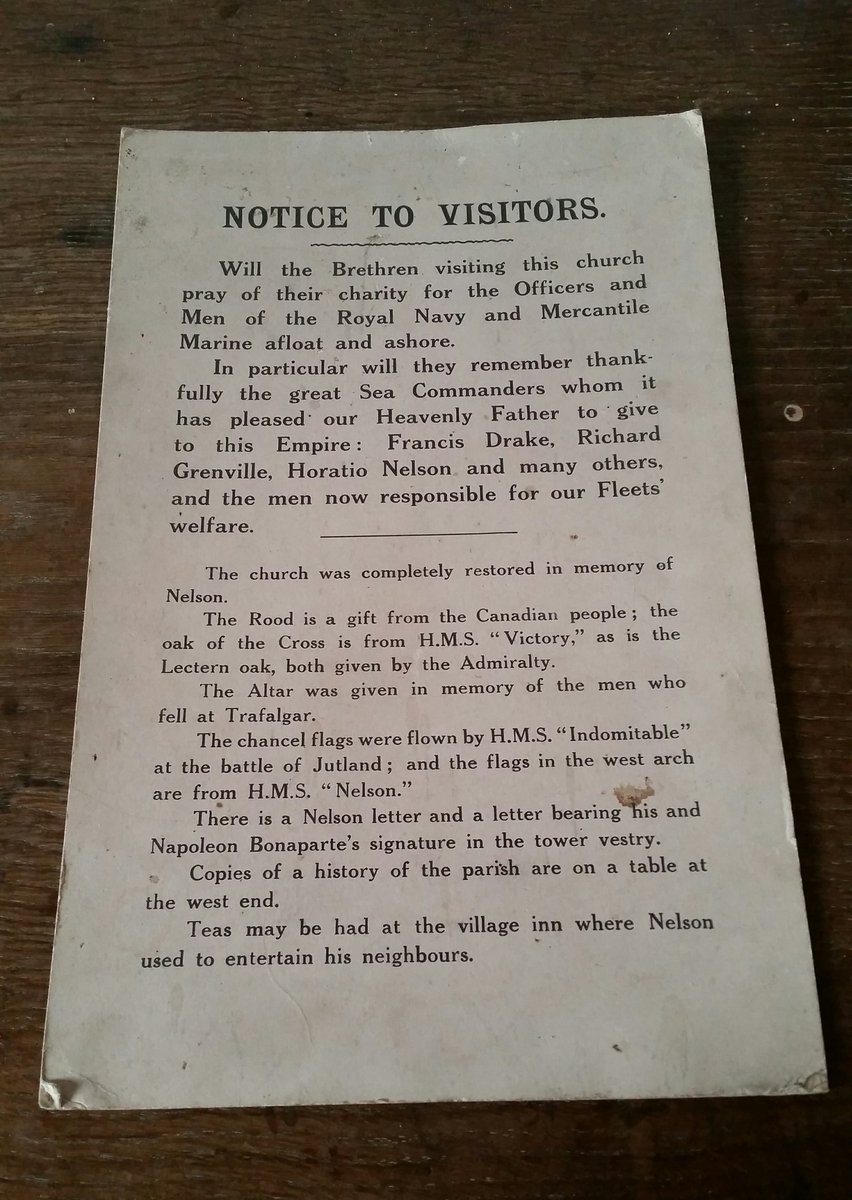

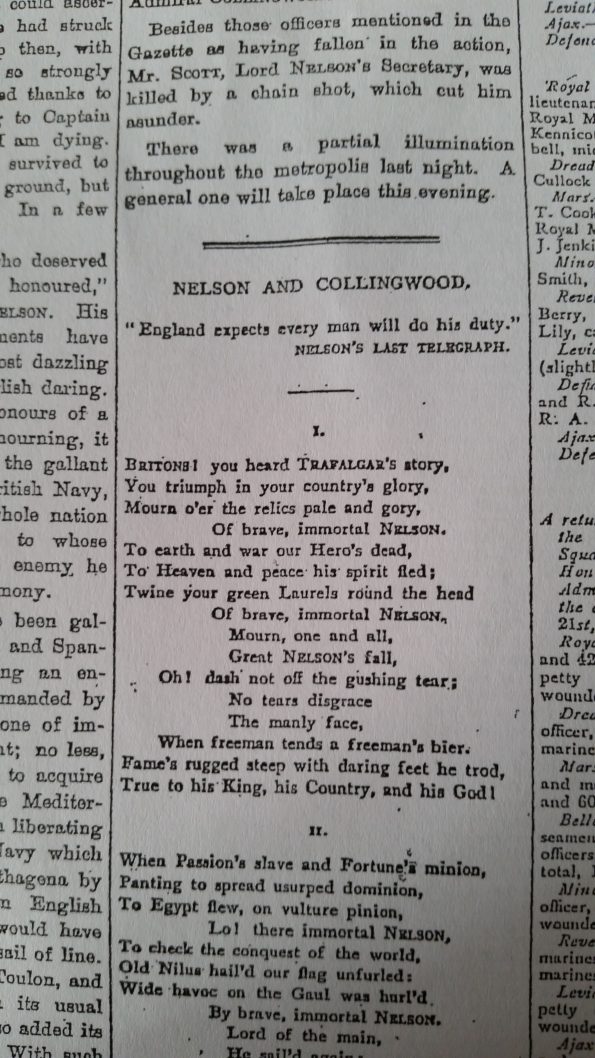

As well as the numerous objects and materials from famous battleships, there are lots of reproduction documents and images hanging on the walls or lying on table tops for visitors to read. These include: Nelson’s baptism record from the church registry; two marriages for which Nelson stood witness; and newspaper reports of Nelson’s death and state funeral. The inclusion of these documents in the church was a thoughtful touch because they provide extra context for those visitors who may not know a great deal about Nelson’s close relationship with this village, or the details surrounding his death and funeral. It is a curious thing, but I sometimes overhear people expressing surprise at the survival of newspapers and ephemera. Given how much of this type of information is now freely available online, this response often surprises me.

- Notice to Visitors

- Reading some reports

- Nelson’s death

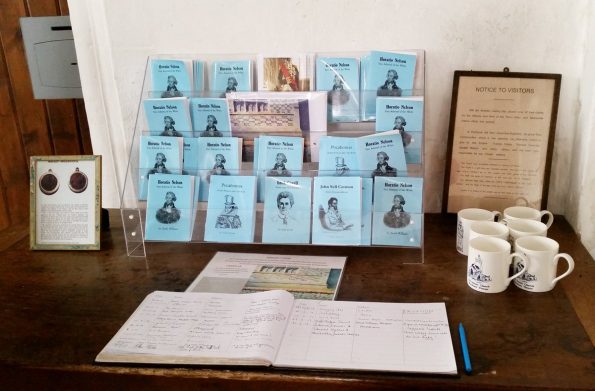

There was a rather quaint selection of gifts, including mugs and mini-biographies, to purchase near the entrance, although I didn’t indulge this time. I did, however, sign the guest book.

The pew cushions were almost all Nelson-themed, which was really quite wonderful to see!

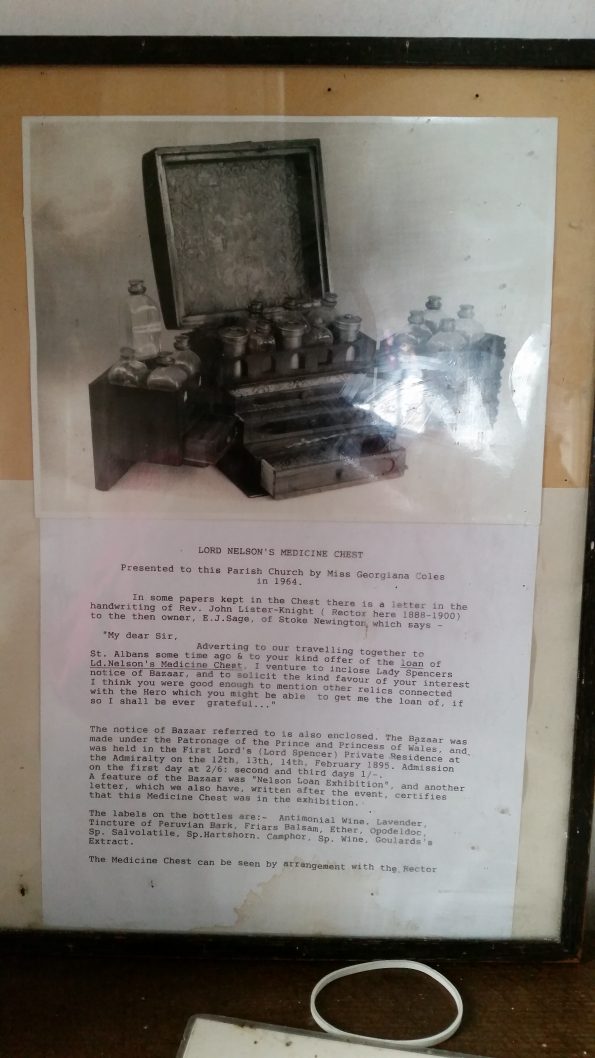

Nelson’s Medicine Chest

While looking through some of the papers and notes displayed in the church, I was surprised to find that the Rector of this parish has Nelson’s medicine chest. It was presented to the church by Miss Georgiana Coles in 1964. The best is not on display, but can be seen by arrangement with the Rector.

According to papers kept in the chest, it was displayed as part of a ‘Nelson Loan Exhibition’ in a Bazaar held in the private residence of the 5th Earl Spencer (1835-1910), the First Lord of the Admiralty, between the 12th and 14th of February, 1895.

The wooden chest contains a number of glass bottles with silver caps

Labels on the bottles reveal that they contain: Antimonial wine, lavender, tincture of Peruvian bark, friars balsam, ether, opodeldoc, sp. sal volatile, sp. hartshorn, camphor, sp. wine, goulards extract. I have no idea what most of these are, or what they are used for.

Any medical historians know more about these medicines and their medical uses in the early 19th century?

Nelson’s relatives buried at All Saints’ Church

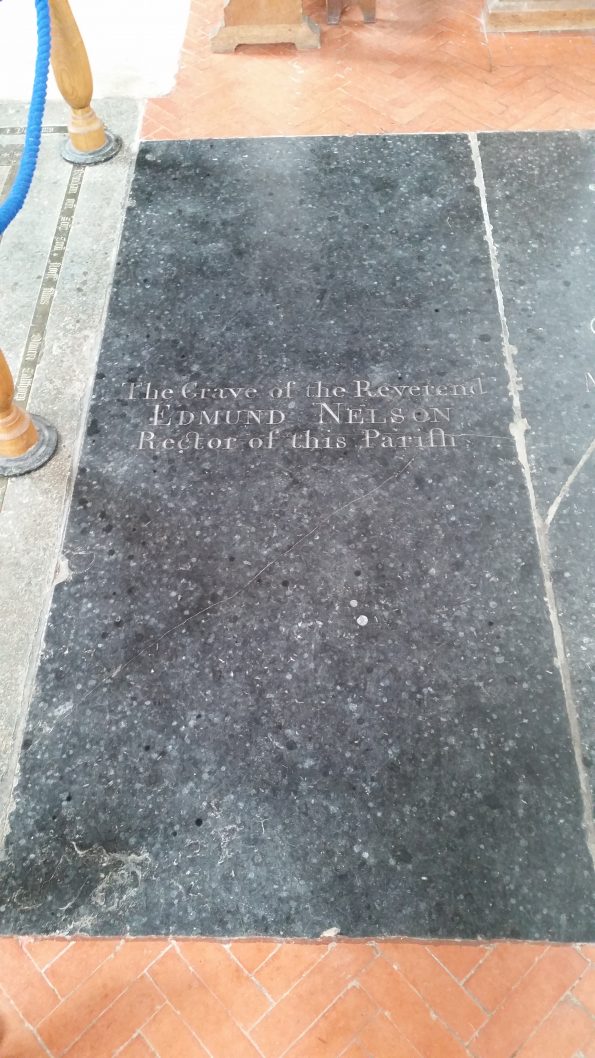

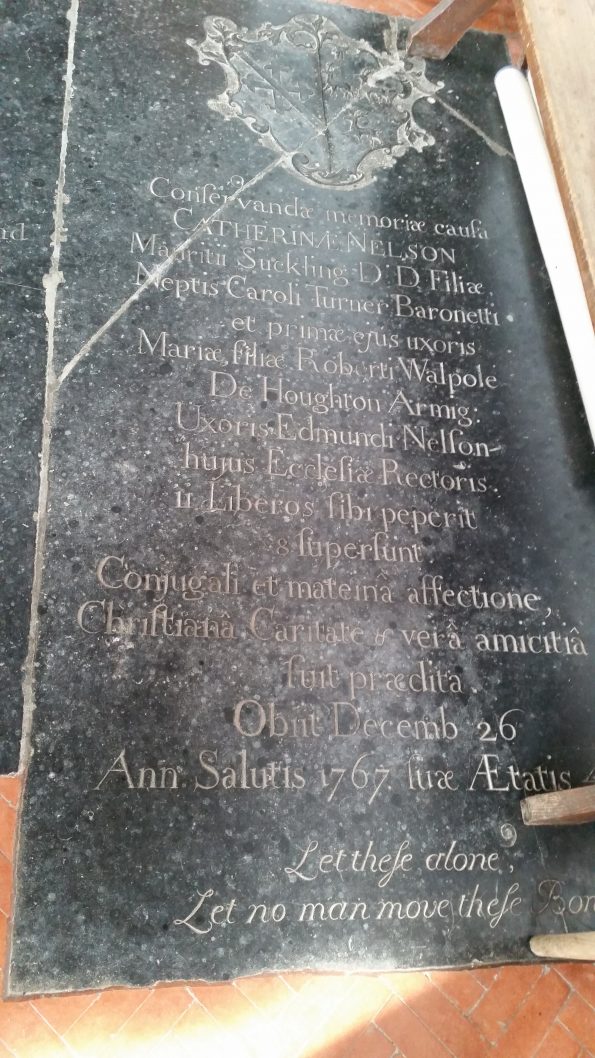

Nelson’s parents and his brother Edmund are buried inside the church, in front of the altar, while his siblings Maurice and Susannah are buried in the churchyard, to the left of the church entrance.

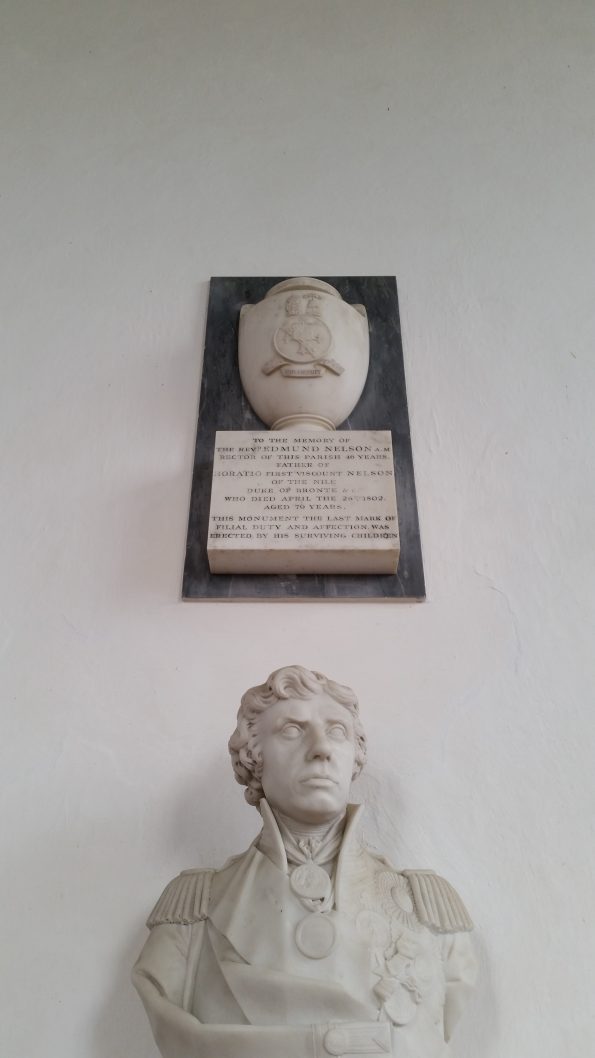

- Memorial to Nelson’s father above Nelson’s bust

- Edmund (father)

- Catherine (mother)

- Susannah (sister)

- Maurice (brother)

- Edmund (brother)

A white marble bust of Nelson looking decidedly stern, or, perhaps, resolute in the face of the French threat, while dressed in his military uniform and wearing his medals, sits above his parents’ graves. According to the inscription on its base, the sculpture was erected by the London Society of East Anglians in 1905, the centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar and, of course, Nelson’s death.

- ‘Who’s that?’

- ‘Nelson!’

- ‘Interesting…’

Before we left the church, I took the opportunity to sign the guestbook. Did I get Nelson’s famous words wrong? Why, yes, yes I did. But you’ll have to go and take a look for yourself.

Nelson’s final resting place. Hint: not at Burnham Thorpe

According to a letter he wrote on board HMS Victory in 1804, Nelson assumed he would be buried at All Saints’ Church. However, his funeral, burial place, and coffin, were to be rather more spectacular than he may have imagined.

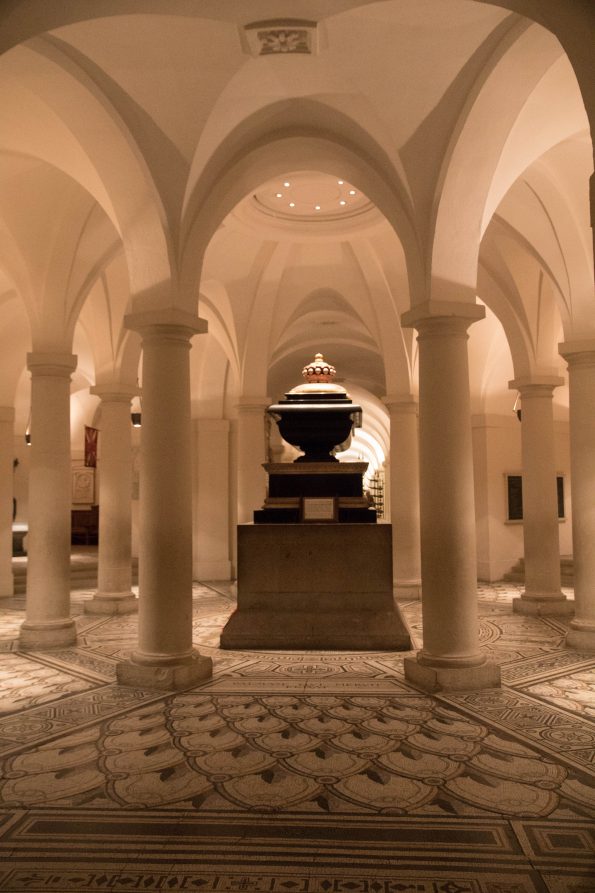

After his death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Nelson’s body was brought to London on board HMS Victory, and he was accorded a full state funeral that last more than five days. After lying in state in the Painted Hall of the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, London, so that people could pay their respects, his body was transported to St Paul’s Cathedral in a funeral car resembling HMS Victory. Thousands of people lined the streets to watch Nelson’s funeral procession. He was buried in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. Nelson’s coffin and sarcophagus were no less spectacular than his funeral car. His coffin was made from the French flagship L’Orient which was destroyed at the Battle of the Nile (1798), and the black marble sarcophagus which sits above his body was originally made centuries earlier for Cardinal Wolsey (1473-1530), but later presented by George III for its current use.

This sarcophagus has a long and interesting story of its own. Wolsey, Lord Chancellor under Henry VII, commissioned an elaborate tomb for himself but after failing to secure an annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he was stripped of both his office and property - including those parts of his tomb that had been completed. Instead of being buried amidst marble splendour at Windsor, his body lies in the grounds of Leicester Abbey (now Abbey Park) marked by a simple, inscribed gravestone which you can still see. Notably, Henry VIII planned to use Wolsey’s tomb, including the sarcophagus, for himself, but it was not completed in time.

If you would like to see Nelson’s final resting place, you can visit St Paul’s Cathedral… or hire the ‘Nelson Chamber’ for a drinks reception for yourself and 249 of your closest friends. Yes, really.

As with other national heroes, many of his personal effects from the time of his death were preserved and some are on public display. The bullet which killed Nelson, for example, found its way into the royal collections and is currently exhibited in a cabinet filled with curiosities outside The Waterloo Chamber at Windsor Castle. The uniform in which he died, still stained with the blood of his secretary, John Scott, is also on public display in the new ‘Nelson, Navy, Nation’ gallery at the National Maritime Museum. The gallery is superb and well worth a visit, although, unlike at St Paul’s, you probably won’t be able to wander around with a glass of wine.

Select Bibliography & links

Richard Holmes (2015) The Napoleonic Wars, Carlton Books.

Martin Robson (2014) A History of The Royal Navy: The Napoleonic Wars, I.B. Tauris.

John Sugden (2014) Nelson: the Sword of Albion, Bodley Head.

Nelson’s funeral - Royal Museums Greenwich - http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/nelsons-funeral

Details about All Saints’ Church, Burnham Thorpe - http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101239270-church-of-all-saints-burnham-thorpe#.WXYJ5RS9jzI

The Nelson Society - http://nelson-society.com

Nelson, Navy, Nation Gallery at the National Maritime Museum - http://www.rmg.co.uk/see-do/we-recommend/attractions/nelson-navy-nation-gallery

‘Nelson’ objects held at the National Maritime Museum - http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;searchTerm=nelson

No Comments