Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821) was born in Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis but spent most of his life in India working for the East India Company as a military engineer and surveyor. He saw action across South India, including at the Battle of Seringapattam (1799) against Tipu Sultan, and also spent two years in Java (1811-1812/13) as part of the British occupation force during the Napoleonic Wars. After his return from Java, Mackenzie was appointed the first Surveyor General of India in 1815. He held this post until his death in 1821.

Mackenzie was interested in the rich history and culture of the lands in which he travelled and worked. He surveyed numerous sites of historical interest, including, famously, the stupa at Amaravati. During his long residence in India, Mackenzie, helped by his local assistants, amassed one of the largest and most diverse collections made here. The tens of thousands of objects in his collection ranged from coins to small bronzes and large stone sculptures, as well as natural history specimens, drawings, and both paper and palm-leaf manuscripts.

After his death in 1821, his widow, Petronella, sold his collection to the East India Company for Rs 100,000. The material was gradually dispersed to numerous institutions in India and the UK, including the British Museum, the British Library, the V&A, the Chennai Government Museum and the Indian Museum in Kolkata.

Catherine Maclean, curator of the Purvai - Warm Wind from the East project based at An Lanntair in Stornoway, had long hoped to bring together material from Mackenzie’s wide-ranging collections for an exhibition in his home town. After a lot of hard work, it was to become a reality when, on 8th May 2017 - the 196th anniversary of Mackenzie’s death - the project received £59,900 of Heritage Lottery Fund money to deliver the exhibition. It was very exciting news because, for the first time in almost 200 years, a selection of Mackenzie’s collections would be brought together from the British Museum, V&A and British Library and travel to his birthplace.

Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle

When I first travelled to Stornoway in April 2016, I had the opportunity to visit Museum nan Eilean in Lews Castle. The castle was in the final stages of a multi-million pound refurbishment and the museum was due to open in July that year. The main galleries were almost fully installed and looked fresh and vibrant. Locally made historic artefacts were juxtaposed with more contemporary material, including a fabulous Harris tweed wedding dress, and an immersive installation introducing visitors to the life and culture of the Western Isles. Alongside these objects were six of the Lewis Chessmen which are on long-term loan from the British Museum. I was also able to see the newly refurbished display space for the proposed exhibition.

Delving into the fascinating history of Lews Castle made me realise just how appropriate this location is for an exhibition focusing on an East India Company officer. The site was originally occupied by Seaforth Lodge, which was built by the 4th Earl of Seaforth in the late 17th century. The 4th Earl’s descendant, the 1st Earl of Seaforth (I know; it’s complicated), was Colin Mackenzie’s patron and helped him to obtain a commission with the East India Company Army in 1783.

Between 1844 and 1851, Sir James Matheson (1796-1878) built Lews Castle on the site previously occupied by the Lodge. Like Mackenzie, Matheson was born in Scotland before travelling to India, but here the similarities end. Matheson, with his partner William Jardine (1784-1843),* formed the company Jardine Matheson & Co. and they made their fortune in the lucrative trade with India and China which included opium. This wealth enabled Matheson to buy the whole of Lewis and build Lews Castle. Lord Leverhulme later purchased Lewis and, some years later, gifted the island and the castle to the Parish of Stornoway. Following this transfer of ownership, the castle was used for different purposes, eventually falling into disuse. It was only in 2011, thanks to a generous HLF grant, that the castle was repurposed and refurbished as a museum and archive, with associated facilities.

* An interesting aside: Jardine had a long business relationship and friendship with Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy (1783-1859). Jejeebhoy was a prominent Parsi-Indian businessman and philanthropist who founded, among other things, the Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art in Mumbai. The company Jardine Matheson & Co., now Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd., remains one of the most successful companies in the world.

Selecting objects for the exhibition

For the exhibition, Catherine was keen to borrow material from the two sections of Mackenzie-related material now held at the British Museum - specifically, a piece of Amaravati sculpture and a selection of coins. It was a pleasure and a privilege to work with Catherine to identify and select this material.

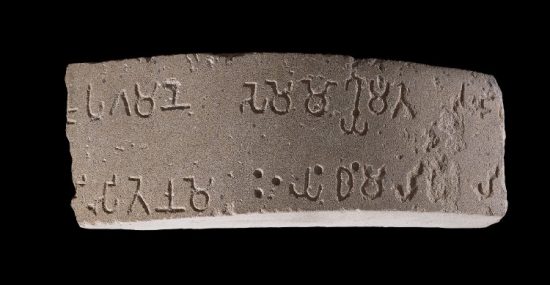

Thousands of coins acquired in India and Java are associated with Mackenzie in the museum. Most are made of bronze and in a fairly worn condition. Coins are, by their very nature, small, portable and generally quite robust objects. In contrast, the Amaravati collection is the greatest collection of Indian sculpture outside India. There are over 120 pieces of sculpture from Amaravati at the museum and, of these, only a limited number can be specifically linked with Mackenzie through drawings made by him and by his assistants at the site. Not only this, but many of the sculptures are delicate and of considerable size, requiring special temperature and humidity controls when on display and in storage.

The chosen objects would not only need to be in good condition and suitable for travel and display, but also visually appealing while fitting the overall narrative for the Collector Extraordinaire exhibition and able to form a dialogue with the other material on display. Selecting appropriate objects for the exhibition, therefore, required careful thought as well as collaboration both with Catherine and a number of colleagues at the museum.

Amaravati

The intricately carved limestone sculptures that once adorned the ancient stupa at Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh, southeastern India, are considered to be among the most accomplished produced in the subcontinent. Built between c.200 BC and AD 250, the Amaravati stupa was rediscovered in the late 18th century by Raja Vesireddy Nayudu, a local landlord, who used many of the bricks and stone pillars for his building projects. Mackenzie first saw the site in 1798, and, when he returned in 1816, the stupa dome had been destroyed and Nayudu had dug out the central part of the mound. As Surveyor General of India, Mackenzie returned to Amaravati in 1816 accompanied by a team of military surveyors and draftsmen and remained at the site for five months. When he left, he issued instructions to his assistants to remain at the site and the survey continued until October 1817. The detailed documentation produced during this extended survey was copied into an album that is now held at the British Library. It contains drawings of individual sculptures unearthed as well as maps of the site, providing precious information about how the mound at Amaravati looked at the time.

A number of stones were removed when Mackenzie was at Amaravati and, in 1845, Sir Walter Elliot began more extensive removals from the site and numerous excavations followed over the subsequent one hundred and fifty years. The slab chosen for loan to the Collector Extraordinaire exhibition was excavated by Elliot, shipped to London in 1859 and, eventually, made its way into the British Museum’s collections in 1880. The panel was previously displayed in the ‘lobby’ of the Asahi Shimbun Gallery of Amaravati sculpture (Room 33a; opened in 1992) located at the western end of the Joseph E. Hotung Gallery for China and South Asia (Room 33) at the British Museum.

- Some of the Amaravati sculptures we looked at in the ‘Amaravati Basement’ store at the British Museum

I looked at the Amaravati sculpture with colleagues from conservation, collection services and the loans team, among others, and discussed various possibilities before eventually selecting this exquisite limestone panel carved with a full vase, called a pūrṇaghaṭa or purnakalasha, which is an auspicious symbol representing abundance. Pūrṇaghaṭa are used in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain ritual ceremonies including, for example, weddings - there was one at my own wedding. They are also employed as decorative motifs to adorn stupas and temples.

Some of the sculptures from Amaravati that depict the stupa itself show pūrṇaghaṭa decorating the stupa dome and on either side of the gateways. However, the style of these pūrṇaghaṭa is very different from the one depicted on the panel on loan. As you can see from the images below, the earlier examples found on the stupa sculpture have wide, rounded bellies decorated with garlands, and thin necks from which emerge curved lotus flowers and buds. In contrast, the pūrṇaghaṭa on display in the exhibition is tall and narrow with bands of beaded decoration and a wide-lipped mouth from which emerge straight lotus flowers and buds, and it is surrounded by elaborate foliage and a beaded border.

Based on these differences in style, it has been suggested that the panel on display may have been produced after AD 250, and perhaps even as late as the 6th century AD. A firm date remains elusive, as does the location of this panel on the stupa. It may have formed part of the architrave of a doorway, or the base of a pilaster, which is an ornamental architectural element that resembles a column, but it may have been employed as decoration elsewhere on the stupa.

- Panel on display, Reg. 1880,0709.68 © Trustees of the British Museum

- Earlier panel Reg. 1880,0709.54 © Trustees of the British Museum

Coins from India, Sri Lanka and Java

During the years he spent campaigning and surveying in India, Sri Lanka and Java, Mackenzie acquired over six thousand coins alongside sculpture, manuscripts and other material. I selected five coins to accompany the Amaravati panel for the exhibition at Lews Castle. Through this selection, I hoped to give the visitor not only an idea of the wide variety of coins found among Mackenzie’s vast numismatic collection, but also about his travels across India, Sri Lanka and Java and some insight into the history of these places.

One of the coins on display, for example, was minted under the authority of the Maharaja of Mysore Krishnaraja Wadiyar III (ruled 1799-1868). After the British defeat of Tipu Sultan, de facto ruler of Mysore, at the Battle of Seringapattam in 1799, the Wadiyar dynasty was restored, albeit with continuing British influence. Mackenzie served as Chief Engineer to the Hyderabad contingent commanded by Col. Arthur Wellesley (later, Duke of Wellington) at Seringapattam, and he was appointed Surveyor of Mysore soon after the end of the war. Between 1800-07, Mackenzie travelled across Mysore with a team of draftsmen, illustrators and translators to obtain knowledge about the geography, geology, history and culture of the region, as well as establishing where the political boundaries lay. During this time, he also amassed a large collection, including this coin.

In 1811, during the Napoleonic Wars, Mackenzie saw service in Java. As Chief Engineer, he was part of the successful British invasion of the island. Alongside his military duties, Sir Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Java, asked Mackenzie to ‘investigate the state of the country’ which meant, in effect, that Mackenzie’s survey encompassed the geography, history and economy of Java, as well as its culture. Once again, in addition to his work, Mackenzie acquired objects, including the 11th century silver ‘sandalwood flower’ coin minted in Java.

Alongside three coins from Mysore, Java and Bengal, I also included two of the seventy* surviving Roman coins in Mackenzie’s collection which were acquired in South India and/or Sri Lanka. My purpose for doing so was two-fold: firstly, many people are not aware of the trade between India and the Roman world; secondly, some rare and valuable information about how Babu Rao, a Maratta translator and one of Mackenzie’s local assistants, acquired Roman coins survives in H.H. Wilson’s catalogue of Mackenzie’s collections. Babu Rao’s reports illustrate not only the extent and duration of the collecting journeys he undertook, but also the wide range of information and objects he encountered and acquired, and his interactions with local people and British officials to achieve his aims.

- I have included almost half of the other Roman coins from Mackenzie’s collection in the Indo-Roman trade section of the Hotung Gallery.

Four of the coins selected for the Collector Extraordinaire exhibition Roman (top left & bottom right), Bengal (top right) and Java (bottom left) © Trustees of the British Museum

Exhibition

The objects all made their way up to Stornoway from London alongside sculpture, drawings and paintings loaned by the V&A and the British Library. Everything was successfully installed and I was fortunate to be among the first to see the exhibition during the grand opening on Friday, 11th August. On the following day, when it was open to the public, I gave a gallery talk focusing on the Amaravati sculpture and coins loaned by the British Museum, while my colleague Nick Barnard from the V&A spoke about the Parshvanatha sculpture and bronzes from India and Java loaned by the V&A. It was such a special moment to stand among and talk about Mackenzie’s collection, his portrait and even his drawings, linking them together for the audience in his birthplace.

It was an extraordinary feat to organise this exhibition, bringing together, as it does, such a wealth of spectacular material from the three institutions, and its success is testament to the hard work of Catherine Maclean and her colleagues at An Lanntair and Museum nan Eilean, and it has been a pleasure to work alongside them on this project.

The Collector Extraordinaire exhibition can be seen at Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle from 12th August to 18th November 2018. I will write a separate blog about the exhibition.

Select Bibliography

David M. Blake, ‘Colin Mackenzie: Collector Extraordinary’, The British Library Journal, pp.128-150.

Jennifer Howes (2002) ‘Colin Mackenzie and the stupa at Amaravati’, South Asian Studies, vol. 18, pp.53-65.

Sushma Jansari (2013) ‘Roman Coins from the Masson and Mackenzie Collections in the British Museum’, South Asian Studies vol.29:2, pp.177-193.

Sushma Jansari (2012) ‘Roman Coins from the Mackenzie Collection at the British Museum’, Numismatic Chronicle vol.172 (2012), pp.93-104.

Robert Knox (1992) Amaravati: Buddhist sculpture from the Great Stupa, London: British Museum Press.

Akira Shimada & Michael Willis (eds.) (2017) Amaravati: The Art of an Early Buddhist Monument in Context, London: British Museum Press.

No Comments