Opening night!

After a slightly frantic start deciding what to wear to an event I had been looking forward to for so long, I donned my sari and headed to the opening of the Collector Extraordinaire exhibition in Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle in Stornoway, Isle of Lewis. The exhibition focused on the life and collections of East India Company officer Col. Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821), the 1st Surveyor General of India. Mackenzie was born in Stornoway but spent most of his life living and working in India. He saw action across South India, including at the Battle of Seringapattam (1799) against Tipu Sultan, and also spent two years in Java (1811-1812/13) as part of the British occupation force during the Napoleonic Wars. It was after his return from Java, that Mackenzie was appointed the first Surveyor General of India in 1815. He held this post until his death in 1821.

Mackenzie was interested in the rich history and culture of the lands in which he travelled and worked. He surveyed numerous sites of historical interest, including, famously, the stupa at Amaravati. During his long residence in India, Mackenzie, helped by his local assistants, amassed one of the largest and most diverse collections made here. The tens of thousands of objects in his collection ranged from coins to small bronzes and large stone sculptures, as well as natural history specimens, drawings, and both paper and palm-leaf manuscripts.

After his death in 1821, his widow, Petronella, sold his collection to the East India Company for Rs 100,000. The material was gradually dispersed to numerous institutions in India and the UK, including the British Museum, the British Library, the V&A, the Chennai Government Museum and the Indian Museum in Kolkata.

For the Collector Extraordinare exhibition, objects from Mackenzie’s collections were brought together from the British Museum, the British Library and the V&A, for the first time since his death. Not only this, but the exhibition is being held in his home town, in the house of his former patron. It is a unique and important exhibition and I am thrilled to be part of it. I have written about my involvement in selecting the objects from the British Museum’s collections for the exhibition in a separate post. It was wonderful to see the Amaravati panel, which is on loan from the British Museum, on display in the exhibition.

Catherine Maclean, Curator of the Purvai Project and the exhibition, introduced her project and the exhibition and received resounding applause for all of her hard work. It was kind of her to mention the help the ‘Mackenzie Super Group’ were able to offer. Of the group, Nicholas Barnard and I were present, and Jennifer Howes will hopefully be able to see the exhibition soon. Alan Gemmell, Director of the British Council in India, spoke about the UK-India Year of Culture and the way in which projects and exhibitions such as Collector Extraordinaire were an integral part of it.

- Alan Gemmell

- Catherine Maclean

Collector Extraordinaire: the exhibition revealed

The objects loaned by the British Museum were perfectly complemented by the drawings and paintings on loan from the British Library, and the range of stone and bronze sculptures from the V&A.

As you enter the gallery, you are welcomed by the enveloping sound of sitar music and the sight of the famous portrait of Mackenzie. He stands with his three Indian assistants and, in the background of the paintings, his surveying basket and pole are set up by the colossal Jain statue of Gommateshwara (Bahubali) at Karkala in Karnataka. Mackenzie wears his military uniform and the red jacket stands out against the well-chosen deep, forest green colour of the gallery walls. The introductory panels provide a useful overview of Mackenzie’s life and his journey to India.

No exhibition on South Asia tends to be complete without an image of the Taj Mahal and here was a detailed painting of the structure from Mackenzie’s collection. It hung above an evocative rendering of the shore temple at Mahabalipuram - about which we heard more from Sona Datta during her lecture the next day.

The Amaravati limestone sculpture depicting a purnaghata (full vase used in Hindu, Jaina and Buddhist rituals) sits alongside a selection of intricate drawings of sculpture found at the site. These drawings are from the Mackenzie Amaravati Album which contains 84 detailed drawings of the sculptures that once adorned the stupa and the railing which surrounded it. One of these is a drawing of a purnaghata panel which is much earlier in date than the sculpture on display. Another is a drawing of a panel on which was carved the whole stupa and part of the railing. If you look carefully at the bottom centre of the drawing, you can see purnaghata on either side of the entrance through the railing.

Displaying these drawings next to the limestone panel provides a useful reminder that the site and its sculpture were not static: both developed over the centuries and the sculptures that adorned the great stupa changed too.

While the British Museum has early panels from Amaravati carved with purnaghata, and drum slabs decorated with views of the stupa and railing, the current location of the panels depicted in the drawings on display are, as yet, unknown.

A plan of the site hangs above the purnaghata panel and 2 drawings. It is inscribed, ‘Plan Descriptive of the Present State of the Mound of Depaldenna at Amravutty Shewing what has been cleared out and what remains to be removed. Laid down from actual Measurements. June 1817. The Yellow Color denote stones that are entirely destroyed. The White whew the place of stones that have been removed & are now missing.’

This rare and invaluable plan remains a key document for scholars today because it provides an accurate and reliable record of the site, including dimensions, which is now utterly dismembered.

A selection of paintings made during Mackenzie’s time in Java were displayed together. Mackenzie spent some two years in Java, having arrived on the island with a British invasion force which included Sir Stamford Raffles. Raffles, the Lieutenant-Governor of Java and later founder of Singapore, encouraged Mackenzie to survey the historic monuments of Java alongside his other duties. Many of the drawings and paintings he and his assistants made are now held at the British Library, and it is from this collection of material that Catherine selected the paintings on display.

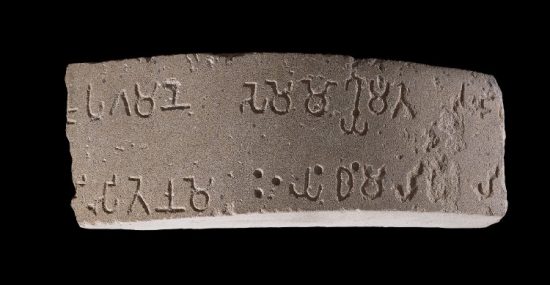

One image (a reproduction is on display) has particular relevance for Scotland. Mackenzie and his surveyors encountered a large inscribed stone during their work in East Java. From here, they dragged it 40 miles to the coast and it was shipped to Calcutta where it was gifted by Raffles to Lord Minto, the Governor-General of India. Minto later shipped the inscription to his family estate in Hawick, Roxburghshire in Scotland, where it still stands.

I include an image of the text panel because all of the interpretation text and labels were bilingual - Gaelic and English - which I thought was great! I did wonder if this might have been the first time some of the descriptions and names of Vishnu’s avatara, Jain tirthankara, as well as descriptions of some of the sites in India and Java were rendered in Gaelic…

- Bilingual panel in Gaelic and English

- Paintings made in Java

- Minto stone

There is a whole wall of paintings from Mackenzie’s collection, and each one is a delight to see in the original. I was especially interested to see a painting of Sarnath because the British Museum holds a number of important sculptures from this site. As part of the Hotung Gallery refurbishment, I have included two large and important c.5th century sandstone figures of the Buddha from Sarnath in the Gupta section and they will be on display when the gallery reopens in November this year. Alongside these sculptures, I also included a photograph of Sarnath that I took when I last visited just a few years ago.

Another painting has a rather more tangential link to an object at the British Museum. It is a view of the Asokan Pillar at Firoz Shah Kotla in Delhi. Firoz Shah Tughlaq (1309-1388), one of the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, moved two Asokan Pillars to Delhi. One from Topra - and this is the pillar depicted in this painting - and a second one from Meerut. Firoz Shah incorporated the Meerut pillar into one of his residences. In the early 18th century, an explosion at this palace broke the pillar into fragments. One fragment was held at the East India Company’s India Museum in Leadenhall Street in the City of London, until it closed. In 1880, it was transferred to the British Museum.

- Asokan Pillar at Firoz Shah Kotla

- Sarnath, the site of Buddha’s First Sermon

A range of other drawings and paintings of historical sites are on display, including a sketch of Manikarnika Ghat in Benares (Varanasi), which is close to Sarnath, and some tombs near Tughluqabad by Delhi. Overall, they serve to show just how widely Mackenzie travelled in India during his life and his particular fascination with the history and culture of this land.

- Tombs near Tughluqabad

One painting is particularly intriguing in terms of the sitter’s possible connection with Mackenzie. It shows a dark-haired woman dressed in white, with feathers in her hair and smoking a hookah under a palm-tree while an attendant holds a parasol over her head to shield her from the sun. Her costume is curious: she wears red slippers, lots of jewellery including necklaces, bangles, anklets, and a bindi, while dressed in a sort of combined salwar-kameez, shawl and blouse with a bizarre headdress made from cloth and colourful feathers. Some think she may be Mary Elizabeth Frederica Mackenzie-Stewart (1783-1862), Lady Hood of the Seaforth family who were Mackenzie’s patrons, while others wonder if she is Mackenzie’s wife, Petronella. The other portrait of Lady Hood shows her to have dark hair, but there are no other known portraits of Petronella, so it is impossible to determine if this painting represents either of them, or another woman entirely. The mystery remains.

While drawings, paintings and the Amaravati panel line the outer walls, the central space is filled with a range of other material from Mackenzie’s diverse collections.

There is a case of coins on loan from the British Museum. These were acquired by Mackenzie and his local assistants across India, including Bengal, Mysore and other regions of South India, Sri Lanka and Java.

One case is filled with small bronzes and one stone sculpture acquired by Mackenzie in South India and now held at the V&A. These are mostly figures originally used in domestic shrines. The figures on display include images of Vishnu, in different incarnations such as Rama, Narasimha and Hayagriva, and a figure of the Jain tirthankara Parshvanatha, as well as a Jain altarpiece showing all 24 tirthankara.

- Vishnu’s Chakra

- Narasimha (Vishnu’s 4th avatara)

- Hayagriva (one of Vishnu’s avatara)

- Ganesha

- Jaina altar with Parshvanatha standing at the centre

One of the most unusual pieces on display is a representation of Parshvanatha carved in green stone, possibly aventurine. He sits on a coil of his yaksha, the serpent Dharanendra who rises up to shelter Parshvanatha with his seven hoods. Green is the colour associated with Parshvanatha, imbuing the sculpture with added significance. Notably, this figure is described in Wilson’s catalogue of the Mackenzie collection (1828, vol.ii, p.ccxlvi, no.98). And, in a case just to the right of the figure, are two drawings of the sculpture from Mackenzie’s collection that are on loan from the British Library. (In case you are wondering, I have used images from the V&A’s online collection website since it was difficult to take good photos of the sculptures because of the reflection from the glass.)

- Parshvanatha image made from green stone

- Reverse of the image showing the serpent Dharanendra sheltering Parshvanatha

Towering above these smaller objects is the spectacular stone sculpture of Parshvanatha, the 23rd Jain tirthankara. Produced between the late 12th to early 14th century, this is one of the treasures of the V&A’s South Asian collections. The gleaming stone surface is so highly polished that it looks like bronze. Unusually, you can walk around the statue and appreciate the restrained accomplishment of the sculptor.

Parshvanatha stands upright in the kayotsarga pose (‘dismissing the body’), sheltered by the seven hoods of his yaksha (nature spirit), the serpent Dharanendra. He is flanked by his attendants, Dharanendra and Padmavati, and the triple umbrella and fly whisks emphasise Parshvanatha’s regal status. The inscription on the base reveals that it was carved in Gulbarga, Karnataka, when the temple in which it originally stood was restored, and even names the ‘stone engraver’ Chakravarti Paloja.

It is on the reverse that the Mackenzie connection is made explicit. ‘C.McK 1806’ is neatly inscribed on the back plate, indicating that the sculpture was originally part of Mackenzie’s collection. ‘Parasa-naat’ (‘Parshvanatha’) is also written alongside Mackenzie’s initials.

- Padmavati (Parshvanatha’s yakshi - female attendant) and part of the inscription.

- Parshvanatha.

- Parshvanatha sheltered by his yaksha (male attendant) Dharanendra’s, and covered by a triple parasol and flywhisks to either side.

Finally, after a whirlwind tour of India and Java accompanied by some of the highlights from Mackenzie’s collection, this intimate exhibition comes to an end with an excerpt of a Gaelic song found in one of Mackenzie’s letters to his patron Lord Seaforth,

‘At the time I wake in the morning, I think of my lass, while missing my kith and kin and the heroes there. Here I find myself in the midst of the Lewes forest, wailing the absence of Hero’s and Chieftains long since departed.’

Mackenzie never did make it back home to Lewis. He died in Calcutta, where his remains still lie in South Park Street Cemetery.

Scottish-Indian feast

Great company at dinner, including Baroness Prashar, Catherine Maclean, Dalbir Singh Rattan, Alan Gemmell, Nicholas Barnard, Sona Datta, David Green and Roopa Panesar.

The restaurant at An Lanntair is serving a special menu during the Purvai events and, after the exhibition opening, we were treated to a wonderful Mackenzie-inspired Scottish-Indian feast. I chose two dishes that, for me, encapsulated Mackenzie’s journey: haggis, neeps and tatties served with a whiskey sauce, followed by South Indian dal, basmati rice and naan. For dessert, it had to be the lemon and pistachio tart. All in all, heaven on a plate.

Gallery talk

The following morning, Sona Datta gave an interesting talk about the temples and monuments of Mahabalipuram (‘Mamallapuram’) on the Tamil Nadu coast. After walking around Stornoway and buying some gorgeous handwoven Harris tweed in a local shop - what can I say, I’m an avid dressmaker! - Nicholas Barnard (V&A) and I had the privilege of giving the first gallery talks in the exhibition.

Focusing on the British Museum’s loans to the exhibition, I spoke about the Amaravati sculpture and the selection of coins acquired in Java and India - both of which I have written about in a separate post.

Starting with the coins, I sketched out Mackenzie’s life and collecting activity in India, Sri Lanka and Java, beginning with his time in Mysore and the Battle of Seringapattam against Tipu Sultan, moving on to his expedition to Java with Sir Stamford Raffles and, finally, Bengal where he died in 1821. The Roman coins provided the perfect opportunity to discuss the important role played by Mackenzie’s assistants in seeking out and acquiring objects for his collection.

Following on from this, I spoke about Mackenzie and his connection to the stupa at Amaravati, as well as the later life of some of the sculptures that were removed from this important site.

Nicholas Barnard introduced the Parshvanatha sculpture, relating the story of this tirthankara and explaining the complex iconography, and he also discussed the small bronzes on display.

Finally, it was time to leave Stornoway and wend our way home. I hope, some day, to return to the beautiful Western Isles.

2 Comments

SHIVA MANJUNATHA

April 20, 2023 at 8:01 amHi Sushmaji, its a beautiful article in that i found one mistake that -Mackenzie stand with other two indian’s it’s not Karkala…..It’s a Shravanabelagola, Karnataka.Thank you!

“As you enter the gallery, you are welcomed by the enveloping sound of sitar music and the sight of the famous portrait of Mackenzie. He stands with his three Indian assistants and, in the background of the paintings, his surveying basket and pole are set up by the colossal Jain statue of Gommateshwara (Bahubali) at Karkala in Karnataka”

Sushma Jansari

April 20, 2023 at 8:42 amHello, and thank you so much for your kind comment! I’m glad you enjoyed the article. I can confirm that the Jain statue is at Karkala rather than Shravana Belagola. It was identified by Jennifer Howes in her book - Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie (1784–1821). New Delhi: Oxford University Press (2010).