In 2009, I started volunteering at the British Museum. I had come across the Masson Project which was run by Dr Elizabeth Errington in the Department of Coins and Medals and was intrigued. The project focused on the collections of Charles Masson (1800-1853; real name James Lewis). He had deserted from the East India Company Army in 1827, took on his pseudonym, and proceeded to travel through north-western India, Afghanistan and beyond into Iran. Between 1833-1838, the EIC re-employed him (without knowing his true identity) to excavate the ancient monuments of south-eastern Afghanistan. During this time, he not only excavated some 50 sites in this region, but also acquired tens of thousands of coins and small objects, including reliquary deposits.

At this time, I knew nothing about the rich Buddhist history and material culture of Gandhara, nor in fact about coins. When I met Liz for the first time and mentioned this, she was remarkably sanguine and asked what I did know. I mumbled something about Roman history and Indo-Roman trade and she presented me with some Roman coins that were from the Masson Collection and also a range of unidentified Roman bronze coins that had not yet been associated with any specific collections. She soon realised that she would have to start with me from scratch.

After a Roman numismatics 101 session with Dr Sam Moorhead, I was let loose on a handful of what transpired to be Nabtaean and Roman coins in Masson’s collection and seventy late Roman bronze coins from an unknown collection. Over a hundred years ago, F.W. Thomas of the India Office Library had described this second group of coins as ‘mere rubbish’. When I first started trying to identify them, I thought he might have been on to something.

What I hadn’t anticipated was a growing fascination with the frankly rather grotty looking late Roman bronze coins. They didn’t fit with Masson’s collection and it was only after some obsessive and relentless detective work that I discovered that they were part of the residue from Colin Mackenzie’s collection. I have written about this rediscovery in two articles - my first ever publications! - but what has so far remained unwritten was how this happened.

I told Liz about what I had found in relation to Colin Mackenzie and his collections, and mentioned the types of coins known to have been among Mackenzie’s numismatic collection. If we were to find Javanese coins among the remaining non-Masson coins, the identification would be secure. She remembered seeing some small silver coins that could possibly be Javanese, so we got down on our hands and knees to look through tray after tray of coins and, right at the bottom, there were indeed some Javanese coins. Eureka! Or, in this case, according to Liz I squeaked in a high-pitched voice, ‘They’re from Mackenzie’s collection!’ or something equally prosaic. This is why I’m a historian and not a script-writer. What I didn’t know then was that, thanks to this rediscovery, I would get to meet some lovely people and eventually travel with them to Stornoway, on the Isle of Lewis.

So, who is Colin Mackenzie?

Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821) was born on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland. After working for the postoffice in Stornoway, he joined the East India Company’s Madras Army thanks to the patronage of the Earl of Seaforth. He arrived in Madras in 1783, aged 30, and his career blossomed. He initially joined the Infantry division, but was soon transferred to the Engineers. Mackenzie saw action across South India, including at the Siege of Pondicherry (1793) and the Battle of Seringapattam (1799) against Tipu Sultan, and also spent time in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka; returned in 1796). Between 1811-1812/13, he was stationed in Java as part of the British occupation during the Napoleonic Wars. It was in Java that Mackenzie married Petronella Bartels, who was born in Sri Lanka and was of Dutch ancestry. In 1815, Mackenzie was appointed the first Surveyor General of India, a post he held until his death in 1821.

Portrait of Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821) with three of his assistants, by Thomas Hickey (BL - F13), at the British Library

Mackenzie was interested in the rich history and culture of the lands in which he travelled and worked. He surveyed numerous sites of historical interest, including, famously, the stupa at Amaravati. During his travels, he also amassed a vast collection of objects, ranging from coins to small bronzes and large stone sculptures, as well as natural history specimens and manuscripts. His local assistants, the brothers Kavelli Ventaka Boria and Venkata Lechmiah, and Dhurmiah (various spellings of all names), were invaluable to him in his acquisition of knowledge and objects.

Upon his death in 1821, Mackenzie was buried in South Park Street Cemetery in Calcutta (now Kolkata). His widow, Petronella, sold his collections to the Bengal Government for Rs 100,000. Horace Hyman Wilson (1786-1860), the Sanskrit scholar, wrote a catalogue of Mackenzie’s collections in two volumes: Mackenzie Collection: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Oriental Manuscripts, and other articles illustrative of the literature, history, statistics and antiquities of the south of India; collected by the late Lieut.-Col. Colin Mackenzie, Surveyor General of India, Vol. 1, (Calcutta: 1828) and Vol. 2 was published in 1828. Wilson was helped in this endeavour by Lachmiah.

Many of Mackenzie’s documents, manuscripts and artwork are now held among the Oriental and India Office Collections of the British Library, and the Government of Madras Library. Those objects that have been identified as associated with Mackenzie are now held at the V&A, the British Museum and the Government Museum in Madras. It is at the British Museum that some of the celebrated Amaravati sculptures linked with Mackenzie are displayed in the Asahi Shimbun Gallery, and where I encountered part of his numismatic collection.

The story continues… first, a Study Day at the British Museum in 2012

Having started the process of researching Mackenzie’s coins, I was keen to learn more about him and his collections. To this end, with the support of Liz Errington and other colleagues in the Department of Coins and Medals where I was volunteering, I co-organised with Paramdip Khera a study day where those who were working on Mackenzie could gather and share their knowledge. This took place in the Dept. C&M on Wednesday, 18th July 2012. It was wonderful to bring together and meet colleagues from other institutions and learn more about their work.

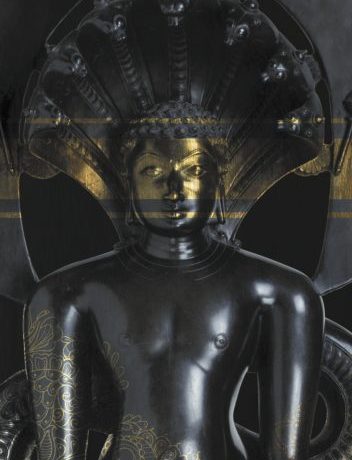

Nick Barnard (Curator South Asia, V&A) presented his research into Mackenzie’s small bronzes and spectacular Parshvanatha sculpture at the V&A.

Dr Jennifer Howes, who has worked on Mackenzie’s collections at the British Library and published a number of articles based on this research, and a book Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie (OUP, 2010). Details about Jennifer’s work, including information about her publications, can be found on her website.

Cam Sharp-Jones spoke about her research into Company School artwork, which included material from the Mackenzie collection.

Paramdip Khera and I presented some of Mackenzie’s coins. Paramdip worked on the Masson Project and had painstakingly identified the many hundreds of non-Roman Mackenzie coins.

Attendees included: Liz Errington (Masson Project, Dept. C&M), Joe Cribb (retired Keeper of the Dept. of C&M, British Museum), Helen Wang (Curator East Asian Money, British Museum), T. Richard Blurton (Curator South Asia, British Museum - and my future manager!), and Henry Noltie (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh).

… and then a panel at the BASAS 2013 conference

Following on from the successful study day, Nick, Jennifer, Cam, Paramdip and I had a panel focused on Mackenzie accepted for the BASAS (British Association for South Asian Studies) conference at Leeds in 2013. It was a great opportunity to share our work with others.

It was here that I first met Catherine MacLean (Curator Purvai, An Lanntair) and learned about her project Purvai - Warm Wind from the East. The Purvai project, based in Mackenzie’s hometown of Stornoway, was inspired by the life and collection of Colin Mackenzie and ‘embraces traditional and contemporary art, music, textiles, literature, history and culture, charting areas of shared humanity between Gaelic culture and the Indian sub-continent. It thrives on the exchange of artists and ideas.’ It was thanks to Catherine that I had the opportunity to travel to the Isle of Lewis in 2016 and visit Mackenzie’s home and mausoleum…but that is for another blog post.

This overall experience was an invaluable introduction to museum-based research, and it had a profound influence on my future career and research aspirations. I thoroughly enjoy collaborative work, a key part of museum-work, and this is something I have continued. The dual approach to material culture - objects and collection history - informed my doctoral thesis and remains integral to my work.

Select bibliography on Col. Colin Mackenzie

Jansari, S., ‘Roman Coins from the Masson and Mackenzie Collections in the British Museum’, South Asian Studies vol.29:2 (2013), pp.177-193.

Jansari, S., ‘Roman Coins from the Mackenzie Collection at the British Museum’, Numismatic Chroniclevol.172 (2012), pp.93-104.

Howes, J., Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie, New Delhi: OUP (2010).

Howes, J. ‘Colin Mackenzie, the Madras School of Orientalism, and Investigations at Mahabalipuram’, in T. Trautmann (ed.), The Madras School of Orientalism: Producing Colonial Knowledge in Colonial South India, New Delhi: OUP (2009), pp.74-109.

Howes, J., ‘Colin Mackenzie and the Stupa at Amaravati’, South Asian Studies vol.18 (2002), pp.53-65.

Blake, David. M., ‘Colin Mackenzie: collector extraordinary‘, British Library Journal (1991), pp.128-150.

No Comments