I often receive emails from students and early career scholars in the UK and abroad who are thinking of entering the museum sector in a curatorial capacity, or who have made tentative steps towards a museum-based career. Many of the questions are quite similar: they generally ask how I became a curator and any advice I might have for those seeking to work in a museum. In this blogpost, I answer the most common questions I receive.

If you do have any questions that I haven’t covered here, do get in touch and I’ll add them into this blogpost.

Proviso: There are as many paths to enter the museum sector as there are people and there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way. This blogpost simply covers the way I worked my way to the post I currently hold. Also, it’s important to bear in mind that although many people tend to focus on the role of curator, it is only one of the many, many different and exciting positions available across the sector in the UK and abroad.

1. How did you come to curate the South Asia collections at the British Museum?

Short answer: In a roundabout way.

Long answer: While studying Graeco-Roman history as an undergraduate, I became increasingly interested in the ancient connections between India and the Mediterranean world. For my MA thesis, I explored the intellectual links that were created through the trade between India and the Roman world across the Indian Ocean. For my PhD, I continued work on East-West relations in antiquity through objects and in terms of literary sources, while also seeking to better understand the (re)construction of historical contact and interaction during the colonial period.

Alongside my academic research, I had been steadily gaining experience working with South Asian objects at the British Museum, first in a voluntary capacity in the Department of Coins and Medals, and then in a paid curatorial role in the Department of Asia. I researched, lectured and published on these collections while also beginning to look more closely at the wider collecting history of this material. As my knowledge and experience developed, and I shared the ongoing results of my work with colleagues, so too did opportunities to apply it in different ways, including a major galley refurbishment.

With hindsight, it is possible to see a strong thread linking all of these different roles and research experiences and I was moving inexorably towards curating South Asian collections. But, when I was starting out, I was mostly looking for opportunities that I found particularly interesting and made the most of them. Each of these led to another and another until I arrived at my current position which, I have to say, is unquestionably the job of my dreams.

2. Do you need an Art History degree? What about Museum Studies or Community Planning?

Short answer: No.

Long answer: The answer to this question depends on the type of curatorial work you aim to do. If you would like to work primarily with South Asian collections, then art history would provide you with a good introduction to and understanding of the wide-ranging sculpture and paintings which tend to make up the bulk of this material. Then again, a grounding in history, anthropology or archaeology, for example, would also give you an excellent baseline from which to approach such collections and research them in a variety of ways. For my part, I am a historian although art history plays a role in my research.

It’s important to remember that as museum funding continues to decrease, curators are increasingly being called upon to curate ever larger and more wide-ranging collections. So, while most curators have a specific area of expertise, it is essential to have – or have the potential to quickly develop – general knowledge about temporally and geographically diverse collections.

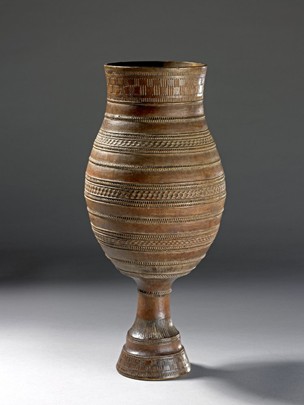

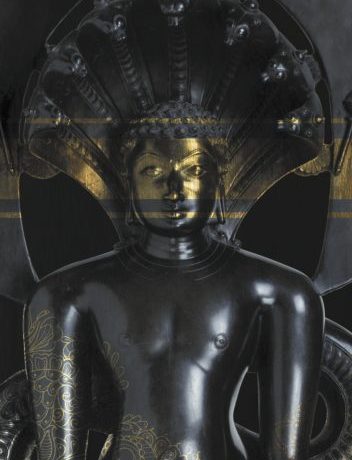

To give my own role as an example, I look after all of the ancient to medieval South Asia collections and most of the South Asian ethnographic collections as well. The 15,000+ objects (I haven’t formally counted yet) range from Palaeolithic hand-axes to the Indus valley collections, alongside almost 2000 years of stone and metal sculpture, and 19th and 20th century ethnographic objects from across South Asia.

I am also asked if studying Museum Studies or Community Planning, for example, would be helpful in pursuing a curatorial career. Once again, this depends on the type of curatorial work you are aiming to do and also the type of institution that you are hoping to work in. At most of the national museums in the UK, the curatorial focus is still primarily on academic research, while many other museums have a broader definition of the role and curators undertake a more wide-ranging function in the institution. However, this is changing all the time. Once you identify the type of work you would like to do, it would be helpful to speak to people who are currently doing that particular job to see what they see as the key skills and academic background that is necessary at present and how they see this skillset changing in the future.

It’s also worth thinking about whether or not the financial cost of the education balances with the realistic, low salary you are likely to earn in the museum sector in the UK and whether there might be funding available to cover the cost of your studies. I studied part-time while working part- and then full-time, and I also received 50% discount on my tuition fees because I worked at the institution in which I was studying. It is also worth exploring whether specific funded training or vocational qualifications might be more directly related to your future career, whether you are already in post or planning to apply for jobs.

3. Do I need a PhD to be a curator?

Short answer: No.

Long answer: It depends on the institution and how they see the role of curator. In recent years, as the competition has increased for an ever diminishing supply of jobs, institutions have extended the list of qualifications and experience in job descriptions. Where previously a degree might have been requested, now a PhD is sought. I’m sorry to say that this situation doesn’t show any signs of changing.

At the museum in which I work, academic research and obtaining funding through this type of research is a key part of curatorial work. Indeed, it is written into my job description. This wasn’t always the case and for the previous generation of curators one of the primary research focuses was writing collection catalogues, while connoisseurship was also important part of their work and approach.

If you are thinking of pursuing a PhD, I would recommend seeing what opportunities are available through the AHRC-funded Collaborative Doctoral Partnerships (CDP) scheme. These projects are undertaken in partnership between Higher Education Institute (HEI) and a museum, library, archive or heritage organisation that is part of the CDP consortium. In practical terms, this means one of your supervisors will come from a HEI and the other from museum, library, archive or heritage organisation, and you will get practical experience researching and working with objects and/or archives while undertaking your PhD. A colleague from Brighton University and I are currently co-supervising a student who is researching the South Asian collectors and donors at the British Museum and I can see first hand just how valuable this broad experience is. Here is a link to the CDP scheme - https://www.ahrc-cdp.org At the top of the page in a bright yellow cardigan, you will see a photograph of one of the curators at the British Museum who is about to complete a CDP PhD.

3. How important is volunteering?

Short answer: Potentially important.

Long answer: This is a difficult question to answer. Personally, I found volunteering immensely helpful and rewarding because I had the opportunity to work on a particular collection and learn a lot about numismatics - a subject that is rarely, if ever, taught as part of university courses at any level either in the UK or abroad. I also gained practical experience working with objects and was supported while researching and publishing my work.

With Robert Bracey and Elizabeth Errington (with whom I volunteered) and Joe Cribb (former Keeper of C&M).

On the other hand, it was very difficult financially and in terms of time. While I was volunteering for 1 day per week, I was also working part-time for 3 days per week and studying for my PhD, while teaching as a Postgraduate Teaching Assistant for one year. The result was that I rarely had any time off and was exhausted. Admittedly, it became even more challenging when I started working full-time while studying part-time and, on top of it all, had a baby, but that’s a different story altogether.

Overall, volunteering has to work for you as well as the institution you are volunteering with. It can be fantastic if you are gaining skills and knowledge that are difficult to develop any other way, and if you have the support and resources to volunteer your time. However, in an environment where funding is decreasing, some institutions are turning to their volunteers to fulfil roles that were previously filled by paid staff and taking advantage of a seemingly endless supply of volunteers, most of whom are desperate to find paid work in the sector.

Understandably, some people are opposed to offering their labour as volunteers without pay. If you are keen to gain experience in the sector and volunteering is either not financially viable or does not work for you for other reasons, there are paid training opportunities available if you look for them. One example, from 2016, was the Strengthening our Common Life (SOCL) heritage skills training programme established by Cultural Co-operation, but there are others.

4. How can I become a volunteer?

Short answer: with perseverance.

Long answer: This was a question that I was asked repeatedly during a recent career event for undergraduate students studying History at UCL. There are many and various ways to become a volunteer and it really depends on what sort of experience you are hoping to gain and the institution in which you would like to gain it.

Be focused. In a time of decreased funding for museums, fewer and fewer staff are called on to do more and more work. So, if you send in a generic email to a curator or any other member of staff asking for some volunteer or work experience, it is unlikely you will receive a positive response, and some may not reply at all. So, think carefully about the following points before selecting any institutions or individuals to contact and address them in your email: 1) why you are emailing them in particular; 2) what you would like to do, when and for how long; 3) what you can bring to the role.

Some institutions, including the British Museum, have specific departments geared towards their volunteers. Be aware that there is often a lengthy waiting list to become a volunteer because there are so many people getting in touch to gain this type of experience. Once again, it helps to be specific about what you want. Here is a link to this department: https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/volunteers.aspx

I do appreciate how challenging it can be to study and volunteer, and it’s especially hard if you are working as well. My advice is to merge aspects of your studies, work and volunteering as far as possible so that they complement each other while moving you in the direction you want to move in, in terms of your future work aspirations. Also, make the most of your holidays by doing a short period of volunteer work either in a single slot or over the course of your holidays during the year. It’s easier to train someone up so they can come back and continue working on a range of projects over a longer period of time.

Many universities have their own museum(s). UCL, for example, has an extraordinary range of collections and museums, most of which are either onsite or within walking distance of the Bloomsbury campus. There are often local city or town museums near universities that you can also approach. Don’t forget learned Societies, many of which also have collections and/or archives.

5. Where can one look for jobs in museum curation and research, especially at the entry level?

Short answer: Everywhere!

Long answer: There are lots of places in the UK that advertise museum curation and research positions in the museum sector, including:

University of Leicester Jobs Desk - https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/museumstudies/JobsDesk

Museum Jobs - http://www.museumjobs.com/

National Museums - https://www.nationalmuseums.org.uk/jobs/

Jobs.ac.uk - https://www.jobs.ac.uk/

It is always worth joining Facebook groups, email lists and following museum-based individuals and institutions on Twitter. This is also where your network - virtual or personal - comes in handy because it is yet another way to learn about jobs that might be coming up or recently advertised.

6. What is your favourite part of working as a curator? What are some challenges that you face as a curator?

Short answer: Objects!

Long answer: Working with, researching, talking about, displaying and sharing objects as widely as possible through different media while working collaboratively is the best part of my job. I could go on, but this is the core aspect of my work and it brings me great joy.

Low pay is a daily challenge.

2 Comments

Laura

July 21, 2023 at 8:05 pmHi Sushma,

I’m very late to commenting on this post, but I just wanted to express how wonderfully informative and eloquent this post was! I’m living in London to gain experience as a museum assistant before I move back to Melbourne, and your answers to some big questions has re-invigorated my excitement to enter and work in the museum curating industry. Thank you for your excellent words!

Sushma Jansari

September 15, 2023 at 9:15 amHi Laura,

Thanks so much for taking the time to leave a reply! I’m so glad you found the post helpful. Good luck with your career!

Warmest wishes,

Sushma