The British Museum Siberian collections are substantial - numbering some 1400 objects – and they also range widely in terms of material, type, and date of production. The earliest objects are stone tools dating to about 3000 - 2000 BC, and the most recent is a mammoth ivory sculpture made in 2010 and donated to the Museum in 2015. All of these objects are held in different departments of the museum. For example, the Department of Coins and Medals has over 600 banknotes, bonds, cheques and tokens issued in different parts of Siberia between about 1917 and 1999. The majority of the Siberian objects, however, are held in the Department of Asia, and it is in the Asian Ethnographic Collections that the Sakha material is found. For a fuller account, including details about all of the Sakha objects in the collections discussed below, see my article on the Sakha Collections.

Sakha Collections

There are approximately 600 objects from Siberia in the Asian Ethnographic Collections and some of these are from Sakha (Yakutia). Of the objects from Sakha (Yakutia), the majority are from Sakha and Tungus (now known as Even or Evenk) communities and most were acquired by the British Museum during the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The Museum did not commission collections to be made in Siberia. Instead, the institution purchased material on an ad hoc basis.

Much of the Sakha material at the British Museum comprises small, easily portable objects. This is because most of the objects were brought back from Siberia as souvenir pieces and many are made from mammoth ivory – a material for which Siberia is particularly well known. The majority of the Sakha material was purchased from individuals such as Kate Marsden and Bassett Digby who had travelled to Siberia and personally acquired the objects they later sold to the Museum. The more recent material donated by Professor Gorokhov and Mr Mamontov was also personally acquired and crafted in Sakha (Yakutia). Notably, however, the first Sakha objects to enter the Museum’s collections were not acquired directly from Siberia, but from the Russian Section of the Paris Exhibition in 1867 by A.W. Franks, of the British Museum.

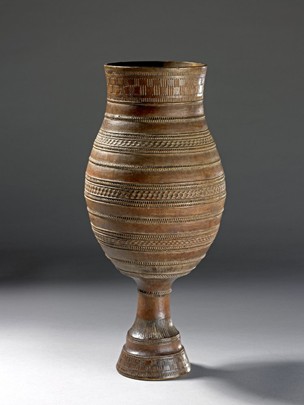

Three trends concerning the Sakha material are immediately apparent. Firstly, the majority of the objects are made from mammoth ivory. Secondly, depictions of Ysyakh, the summer festival, are particularly well-represented, including a model of the event and a comb. There are also two chorons - wooden vessels made to hold kumis (fermented mare’s milk) called choron that are used during Ysyakh. Thirdly, there are comparatively few objects that are generally referred to as ‘ethnographic’. Marsden’s collection stands out in this regard. Unfortunately, however, there are no surviving notes concerning how, where, when or even from whom the objects were acquired, or any details concerning their manufacture or use.

Here, I provide an overview of some of the different collectors and collections from which a selection of Sakha objects came to the British Museum. The information is arranged by collector in date order.

1. Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks

Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826-1897) had a long and distinguished career at the British Museum. He was appointed to his first post at the Museum in 1851 and he held the position of Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography between 1866-1896. He was also one of the Trustees of the Christy Fund. Henry Christy (1810-1865) was a businessman, traveller and collector who bequeathed his large collection, comprising mostly ethnographic objects, to the British Museum. Christy also bequeathed £5,000 to the Museum for the purpose of acquiring more ethnographic material. It was using money from the Christy Fund that Franks acquired the first Sakha objects to enter the British Museum.

On 10 July 1867, Franks wrote to the British Museum Trustees requesting permission to travel to the International Exhibition (also called the ‘Paris Exposition’) held in Paris in 1867 in order ‘to acquire desirable additions for the Christy Collection’. These were to be purchased using the first installment of the Christy Fund, which was £50.

Franks stayed in Paris for almost a month during the summer and made numerous trips to the Exhibition, taking notes and sketching some of the objects that were displayed in the Russian section. His notebook, which survives and is held at the British Museum, includes various objects he purchased and some, including a bow, crossbow and arrows, which he did not. In the notebook, he drew and described the ivory model of the Ysyakh festival and the model dog sledge, which he later purchased for the Museum.

- Model of summer camp (Ysyakh). As.5068.a

- Dog sledge model. As.5068.b

Franks returned to Paris towards the close of the Exhibition to purchase more objects. In a report to the Trustees dated 9 October 1867, Franks referred in general terms to some Russian material he bought. He wrote (in the third person),

Mr Franks made a few small purchases out of the Christy fund and he also selected some very curious specimens from the Russian section - Dresses and implements of the wild tribes of Siberia. He was unable however to get the prices fixed for those objects which belong to the Imperial Domain, and their purchase must depend on circumstances.

The summer camp has been on display a number of times. It was first displayed alongside the rest of the Christy Collection in 103 Victoria Street, London and Franks also mentioned it in his Guide to the Christy Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities and Ethnography (1868).

Most recently, the summer camp model was displayed in the ‘Century Long Journey’ exhibition at the National Art Museum of Sakha (Yakutia). It was also included in the ‘Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’ exhibition (2011) curated by the artist Grayson Perry at the British Museum.

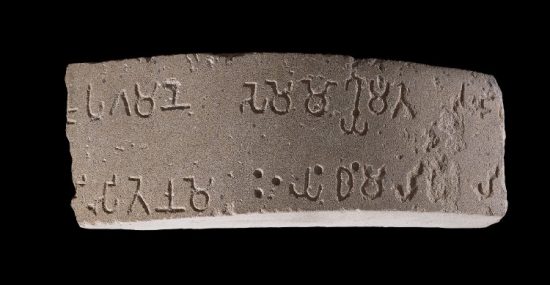

Mr Ronald Bridgett (1839-1899) was the British Consul in Argentina. In August 1867, he arrived at the port of Nicolaievsk at the mouth of the River Amur, and from here he spent two months travelling along the Amur and Shilka Rivers in a steamer ship. During his travels, he acquired a finely carved mammoth ivory comb that he later donated to the British Museum. In a letter he wrote to the Trustees of the Christy Ethnological Museum, dated 11th May 1869, he mentioned that the comb was ‘carved by the Toungouts of Eastern Siberia from the bone of a Mastodon, and obtained by me in the autumn of 1867 at Blagoveshchentz [Blagoveshchensk] on the Armour [River Amur] when ascending that river.‘ He adds, ‘I place it [at] your disposal should you think it worthy of a place in your museum.‘

From this letter, is not clear from whom he purchased the comb, or whether he commissioned it. Bridgett describes it as ‘Toungouts’ (‘Tungus’, now known as Even or Evenk), while more recent analysis by scholars in Sakha (Yakutia) suggests Sakha people may have made it. It is carved with a double-headed eagle at the centre of the comb and a lion and unicorn standing to either side.

Mr William Bragge (1823-1884) was a British civil engineer, businessman and collector. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, the Anthropological Society, the Royal Geographical Society, and numerous other societies in the UK and abroad.

Bragge travelled extensively, especially in Europe, Egypt, South America and Russia. During his travels, he acquired a vast collection of books and objects, many of which are now held in libraries, museums and societies in the UK. Among his collections were approximately 13,000 smoking pipes and other objects associated with tobacco. In his book, Bibliotheca Nicotiana (1880), Bragge lists over 100 objects from Russia, including snuffboxes made from semiprecious stones found in Siberia, such as jasper and rose quartz.

The British Museum holds over 2,000 objects from Bragge’s collections. Most of this material is tobacco-related, but a range of other objects are also included, such as boat paddles from New Zealand, blow pipes from Brazil, a carved ivory box from Nigeria and a mammoth ivory puzzle box made in Yakutsk. This last object is a Chinese tangram puzzle comprising seven flat shapes that fit together to form a square. Inside the box, a note written by Bragge reads, ‘Mammoth Ivory. Carved by a peasant at Yakutsk on the Lena. Siberia. Given me by Col. Zarubin. Jan. 68 [January 1868]. W. Bragge.’

From 1858-1872, Bragge was a managing director of John Brown & Co. Ltd. - a company based in Sheffield that manufactured armour-plate. This particular type of armour-plate was made from a compound of rolled iron with a steel face. It is likely to have been this business that led Bragge to Kolpino, which was the site of an important Russian iron works. An additional note in the Christy Collection Register held in the ALRC at the British Museum bears this out: it notes that Col. Zarubin was ‘Governor of the Iron Works at Kolpino.’

Bragge and Zarubin appear to have become friends during Bragge’s visit to Russia. Among the Christy Correspondence, there is a letter from Col. Zarubin dated January 17, 2023 addressed to ‘Dear Sir’ who is almost certainly Bragge. The letter mentions two parcels that Zarubin has sent to Bragge as a gift - ‘You would please my [sic] very much in accepting the applied two parcel’ - and Zarubin notes that ‘most part of it for you and there is also four picture for [?] Bally [unknown individual]’. He ends by wishing Bragge a ‘very happy voyage’ and writes that he would be ‘very, very much pleased to see you again at the house of a [?] Zaroubin.’ At the end of the letter are two lists: one describing thirteen views of the Kolpino Works; the other describes the objects contained in the parcel he has sent to Bragge, including some tobacco related material. At the top of this list, however, is the tangram puzzle box. Zarubin writes, ‘1) Jakoutsk [Yakutsk] (town in the Asiatic Russia). Game box made of mammoth by common knife.‘

Miss Kate Marsden (1859-1931) was a British nurse and traveller who remains well-known in Sakha (Yakutia). She travelled to Bulgaria to nurse Russian soldiers injured in the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), and was awarded a Red Cross medal for her work. It was in Bulgaria that she first encountered leprosy and, some years later, she decided to dedicate her life to care for those suffering from this disease. She obtained the support of Queen Victoria, and the Princess of Wales presented Marsden with an introduction to her sister, Maria Feodorovna, the Empress of Russia. With the benefit of such patronage, Marsden set out for Siberia in 1891 with the aim of helping the lepers in this region - which she did. A Russian-speaking companion, Miss Ada Field, travelled part of the way with her, but ill health prevented Field from completing the journey. In 1892, having returned to England after her travels, Marsden was elected one of the first female fellows of the Royal Geographical Society.

Marsden described her journey to Siberia and work there in her book, On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers (1892). During her travels in Siberia, she acquired a number of objects, including those she later donated to the British Museum. Marsden describes some of them in her book,

All my riding gear, including the quaint Yakut saddle, made of wood - most inconveniently wide - with a cushion fastened to the top of it, the bridle and reins, and all my own attire I have brought home with me as a curiosity, and also many other things used both in my sledge riding and horseback riding, which all speak plainly of the difficulties under which our journey was accomplished. (page 99)

- Marsden wearing the clothes she wore during her travels in Siberia & a map showing her route

- Marsden travelling in a sledge through Siberia

Also in this book, in connection with the British Museum, she mentions burning soil - smouldering subterranean peat - that she encountered in the forests in Siberia,

I brought home with me some of this burnt earth, intending to send it to the British Museum, should no specimen be already there. (page 103)

The reference is interesting: it shows that during her travels, Marsden was already thinking about and acquiring material she hoped to donate to the British Museum. It also suggests that she carefully selected the seven objects that she did eventually donate to the Museum. It is unfortunate that no documentation concerning this donation survives. In relation to the sample of earth, it is not clear if Marsden offered it to the British Museum and it is not among the objects that were acquired from her. It is possible that it was donated to the Natural History Museum, but a search of their online catalogue did not reveal anything from Marsden.

After her return to London, Marsden gave a number of public talks between 1892 and 1893 about her work and travels in Siberia. During these talks, she used glass lantern slides and showed her audience some of the objects she had acquired there. In 1893, while she was visiting America, she also exhibited some of her objects in the British section of the Woman’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Newspaper reports state that her former travelling companion, Miss Ada Field, was also present. The Chicago Daily Tribune (Sunday, June 18th 1893) describes the high-ranking Russian visitors to her section, and Bishop Nicholas of the Russian Orthodox Church blessed her display, saying,

Your intentions are so high and so pure every Christian man, wherever he may be found or whatever his creed, must appreciate and encourage them. Although your exhibit is a small one, the ideas it conveys and the feelings it is sure to arouse are great and I want to express to you the gratitude of all good Russian people. While you are not an orthodox Greek I am sure you have the heart of a Christian and are engaged in a Christian work.

Numerous newspaper articles mentioned Marsden, her extraordinary travels and work in Siberia, and her display at the Chicago Exposition, as did contemporary books written about the Exposition. According to these reports, the objects in her section ranged from a wooden saddle, fur coat and sample of dry black bread she ate during her journey, to a letter of introduction from the Princess of Wales to the Tsarina, photographs, model of the leper village she helped to set up, model of a leper house, copies of her book which she sold in order to raise money for the village, and a pamphlet she had printed to hand out to visitors.

It is not clear where these objects are now. Interestingly, none of the reports mention any of the distinctive objects she later donated to the British Museum. Given her stated intention to acquire and donate objects to this Museum, it is possible that Marsden put a small collection to one side for this purpose, and for sake-keeping, and did not take them abroad with her.

Mr (George) Bassett Digby (1888-1962) was a British journalist, traveller and collector. He donated some of his acquisitions to national museums in the UK, including the British Museum and Natural History Museum, and the USA. Digby travelled to Siberia twice. The first time was part of a round-the-world trip that he undertook with a colleague, R.L. Wright. They both worked at the Knickerbocker Press in Albany, New York, and their travel accounts were published in this newspaper. During this first trip to Siberia, Digby and Wright visited Yakutsk and the museum in Irkutsk in which the East Siberian Imperial Geographical Society was based. Here, they saw the ethnographical collections and other objects.

Digby returned to Yakutsk in 1914. The reason for this second trip appears to be a search for mammoth ivory on behalf of a businessman: in the acknowledgement to his book The mammoth, and mammoth hunting in north-east Siberia (1926), Digby writes,

I wish to make my acknowledgements to a certain genial and enterprising gentleman who took a sporting chance on my being able to find a big hoard of mammoth-ivory for him.

A collection of photographs titled ‘Ivory Trade in Yakutsk’ in the Martinus Adsbol album show that he located a mammoth tusk yard in Yakutsk that contained large specimens (some of these photographs are published in S.A. Digby 2008). It was from here that Digby acquired a large woolly rhinoceros skull and horn that he sold to the Natural History Museum in London (Registration Number: M10967). While travelling in Yakutsk, Digby collected various botanical specimens and later donated them to the Natural History Museum. He also acquired various mammoth-ivory objects, some of which he donated to the British Museum in 1915. In a letter to the Museum, dated 1 May 1915, Digby supplied information about the birch bark box and figures:

The birch-bark canister thing is particularly interesting I think. It is the only thing of its kind I have seen and neither its possessor nor any of the natives nor the Russians up there knew how to play the game or had seen one before. It was brought to me while I was travelling among the YAKUTI [Digby’s emphasis], giving out that I was interested in starri zoobi (old bones) [the phrase may be ‘Starye zuby’ which means ‘old teeth’]. I gathered that it was very old and the old yakut woman who owned it looked on it as a curiosity. She vaguely shifted the mammoth pieces to and fro as though they were part of a game but seemed to know nothing of the rules. I would point out that the bark “canister” is lined with flaked talc from the north Siberian deposits.

A few days later in May, the Museum formally acquired a selection of objects from Digby, including the box and game pieces, as well as a comb and a small toy. A brief note summarising Digby’s comments are included in the Register, ‘[the game pieces are] said to be very old. The owner [Digby] did not know how the game was played, but look on it as a curiosity.’

6. Mrs T. Kallin

In 1926, Mrs T. Kallin donated a child’s coat made from reindeer fur and pieces of woollen cloth to the museum. Nothing more is known about Mrs Kallin - not even her first name - nor how she acquired this coat.

At some point in or before 1963, L. H. Grantham brought a carved ivory plaque into the museum to show to a curator in order to learn more about the piece. It is an intricately carved, pierce-worked scene depicting the summer festival, Ysyakh. The ivory is likely to be mammoth ivory. Curiously, L. H. Grantham did not return to claim this beautiful object and it was acquired by the museum in 1963. Nothing more is known about this person.

8. Professor Semyon Nikolaevich Gorokhov

In 1997, Professor Semyon Nikolaevich Gorokhov donated to the museum a souvenir mask made in Sakha in the 1990s. It represents a shaman’s mask and is made from multi-coloured pieces of suede that are sewn together with dark brown hair is around the top of the mask and representing a moustache; five light and dark blue leather tassels hang down from the front of the mask with a bone toggle at the end of each tassel.

Prof. Gorokhov kindly presented this mask to the Museum as a gift from Yakutsk when he came to see the model summer camp.

9. Mr Konstantin Merkur’evich Mamontov

Mr Konstantin Merkur’evich Mamontov (b.1949) is an accomplished sculptor and Senior Lecturer at the Arctic State Institute of Arts and Culture in Yakutsk. He trained with the Graphic Art faculty of Novosibirsk State University. In 2010, Mr Mamontov carved a sculpture of a mammoth from mammoth ivory and bone and, in 2015, he generously gave this piece as a gift to the museum.

Acknowledgements

I enjoyed the benefit of numerous conversations with Alison Brown, Tanya Argounova-Low and Eleanor Peers, all at the University of Aberdeen, about the Sakha collections at the British Museum. I would like to thank them for so generously sharing their knowledge with me about the Sakha collections. I was fortunate to meet (the modern!) Kate Marsden who has been researching her Victorian namesake. She was kind enough to share her research with me, and this has informed the section on Marsden in this article. I would also like to thank a number of colleagues at the British Museum who helped me track down invaluable archival material in the Museum, especially Jim Hamill, Francesca Hillier, Gaetano Ardito and Marjorie Caygill.

Select Bibliography

Anderson, M. (2006), Women and the Politics of Travel, 1870-1914, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Bragge, W. (1880), Bibliotheca Nicotiana: A catalogue of books about tobacco, together with a catalogue of objects connected with the use of tobacco in all its forms, Birmingham: Private Print; Hudson & Son.

Bridgett, R. (1869-1875), ‘A Summer Trip up the Amoor River’, in Illustrated Travels: A Record of Discovery, Geography, and Adventure, Vols. 1-2, H.W. Bates (ed.), Paris & New York: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.: London, pp.245-247.

Digby, B. (1915), ‘Mammoth Hunting in Siberia’, The Graphic, 6 March 1915, p.312.

Digby, B. (1916a), ‘Along a great Siberian river’, Travel 25 (June), pp. 18-21, 46-47.

Digby, B. (1916b), ‘Yakutsk - A Siberian outpost’, Travel 25 (July), pp.12-21, 45-48.

Digby, B. (1924), ‘Mammothware’, Manchester guardian 1 February, p.16

Digby, B. (1926), The mammoth, and mammoth hunting in north-east Siberia, London & New York: H.F. & G. Witherby, D. Appleton & Co.

Digby, B. (1928), Tigers, gold and witchdoctors, London & New York: John Lane, The Bodley Head Ltd.; Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Digby, S.A. (2004), Mammoths and wars, travel and home: The geographical life of journalist and natural historian Bassett Digby (1888-1962), unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation (Geography), University of California, Los Angeles, USA.

Digby, S.A. (2008), ‘Early twentieth-century collection of extinct mammals from northern Siberia: the provenance of Bassett Digby’s contributions to the Natural History Museum, London, and the British Museum’, in Archives of Natural History, No.35 (1), pp.105-117.

Franks, A.W. (1868), Guide to the Christy Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities and Ethnography, London: Printed by order of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Graham, F. (1981), ‘Travellers in Siberia’, in Newsletter (Museum Ethnographers Group), No.11, pp.1-11.

Johnson, H. (1895), The Life of Kate Marsden, London: Simpkin.

Manley, D. (2009), The Trans-Siberian Railway: A Traveller’s Anthology, Oxford: Signal Books.

Marsden, K. (1893), On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers, New York: Cassell Publishing Company.

Middleton, D., ‘Marsden, Kate (1859-1931)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2004) [accessed online: 7 April 2017: http://oxforddnb.com/view/article/42348].

Smith, G.B., ‘Bragge, William (1823-1884)’, rev. Carl Chinn (2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2004) [accessed online: 7 April 2017: http://oxforddnb.com/view/article/3223].

Wilson, D.M., ‘Franks, Sir (Augustus) Willaston (1826-1897)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2004) [accessed online: 7 April 2017: http://oxforddnb.com/view/article/10093].

Wright, R.L. and B. Digby (1913), Through Siberia: an empire in the making, London & New York: McBride, Nast & Company; Hurst & Blackett.

Archives in the British Museum

Franks Notebook LS11, relating to the Paris Exhibition of 1867. Held in the ALRC.

Christy Correspondence File, including letters from Mr Ronald Bridgett and Colonel Zarubin. Held in the ALRC.

Letters from Mr Bassett Digby, dated 30th April 1915 and 1st May 1915. Held in the archives of the Department of Britain, Europe and Prehistory.

Officers Reports records series contain the reports to the Trustees of the British Museum by Sir A.W. Franks dated 10th July 1867 and 9th October 1867. Held in Central Archives.

Trustees’ Minutes dated 23rd November 1867. Microfilm of the Minutes are held in the ALRC, and the original volumes are held in Central Archives.

No Comments